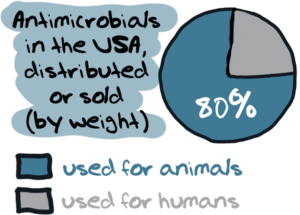

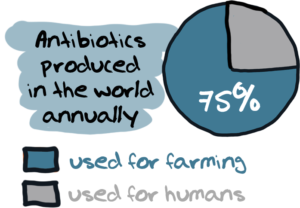

For most people, the term ‘antibiotics’ usually evokes the idea of medicines used for treating human beings with bacterial infections. But many would be surprised to know that – antibiotics are used in even larger quantities in the world of food animals – cows, chicken, pigs, sheep and aquaculture.

For example, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration:

And globally, some 131,000 tonnes of antibiotics are used annually in farming.

Why is this significant at all?

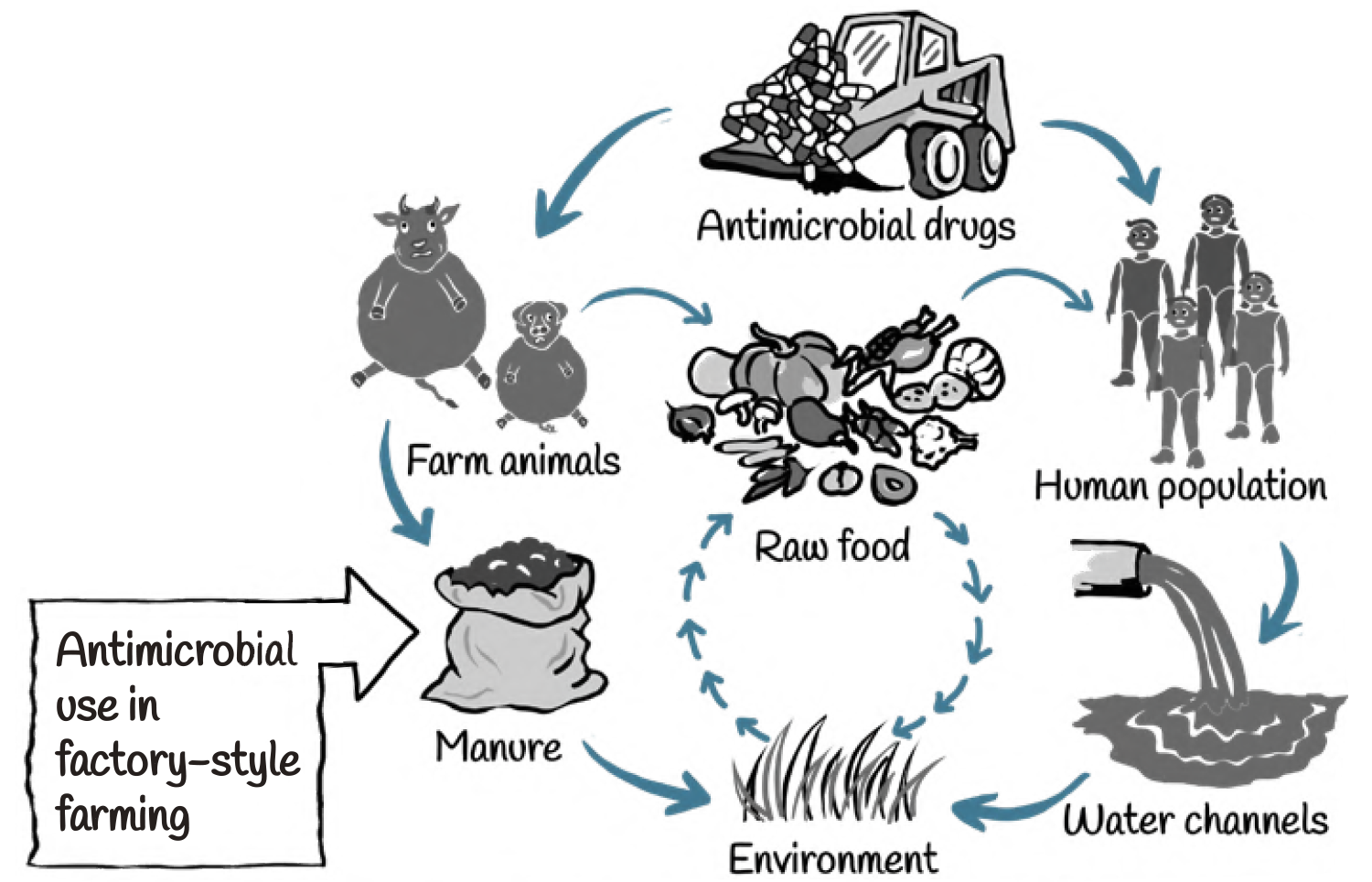

The main reason is simply that the use of antibiotics in animals and the meat industry is also a major driver of antibiotic resistance, which then has consequences for both human and animal health.

Use of antimicrobials, in both human and non-human sectors, drives selection for resistance among bacterial pathogens. Repeated exposure to low doses of antibiotic agents, creates ideal conditions for the emergence and spread of resistant bacteria in animals. Many classes of antibiotics that are used for humans are also being used in food-animals.

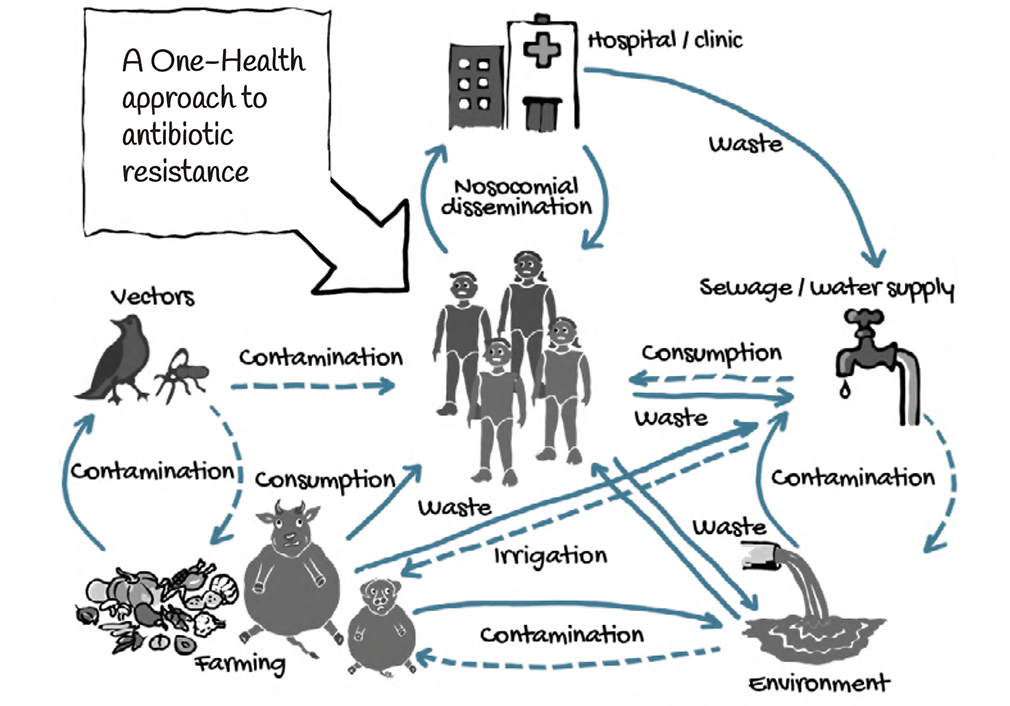

Transmission of resistance from animals to humans can take place through a variety of routes. These include through direct contact, contamination of the environment and through food.

For example, farm and slaughterhouse workers, and veterinarians, who come in close contact with colonized or infected animals, are at risk of carrying resistant bacteria and passing them on to others.

What are antibiotics used for in animals?

The broad purposes for which antimicrobials are used in food-animal production are:

• For therapeutic use i.e. treatment of disease;

• For non-therapeutic use, including prevention of disease;

• For ‘growth promotion’, as they are believed to “help growing animals digest their food more efficiently and allow them to develop into healthy individuals.”

Of all these, ‘growth promotion’ is the most problematic as lot of antibiotics are used for helping the food-animals gain weight. The logic is simple – bigger and heavier the food-animal, more the income for producers. This drive for profit ignores the larger health consequences to everyone due to increased bacterial resistance.

While such use for growth promotion has been banned or restricted in many countries, producers often find other ways of giving antibiotics to their animals, including in guise of ‘prophylaxis’ or preventive treatment.

In the modern industrialized food-animal production, feed for growing animals often gets supplemented with antibiotics in various doses.

Factory-style farming

This rising tide of antimicrobial use is propelled, in part, by the growing demand for animal protein and anticipated increases in industrial food-animal production. Such production involves factory-style farming, in which thousands of animals of one breed and for one purpose are raised under highly controlled conditions.

They are often kept in confined housing, given medicated feeds, and denied access to forage crops. Among the food-animals bred in this manner are pigs, layer hens, broiler chickens, ducks, turkeys, beef or dairy cattle, finfish, or crustaceans.

A study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) attributes one-third of the global increase in antibiotic consumption to the shift towards intensive farming systems and two-thirds as a result of the larger number of food-animals in production.

Rising meat consumption is a major driver of antibiotic use. Growth in global consumption of meat proteins over the next decade is projected to increase by 14% by 2030 compared to the base period average of 2018-2020, driven largely by income and population growth.

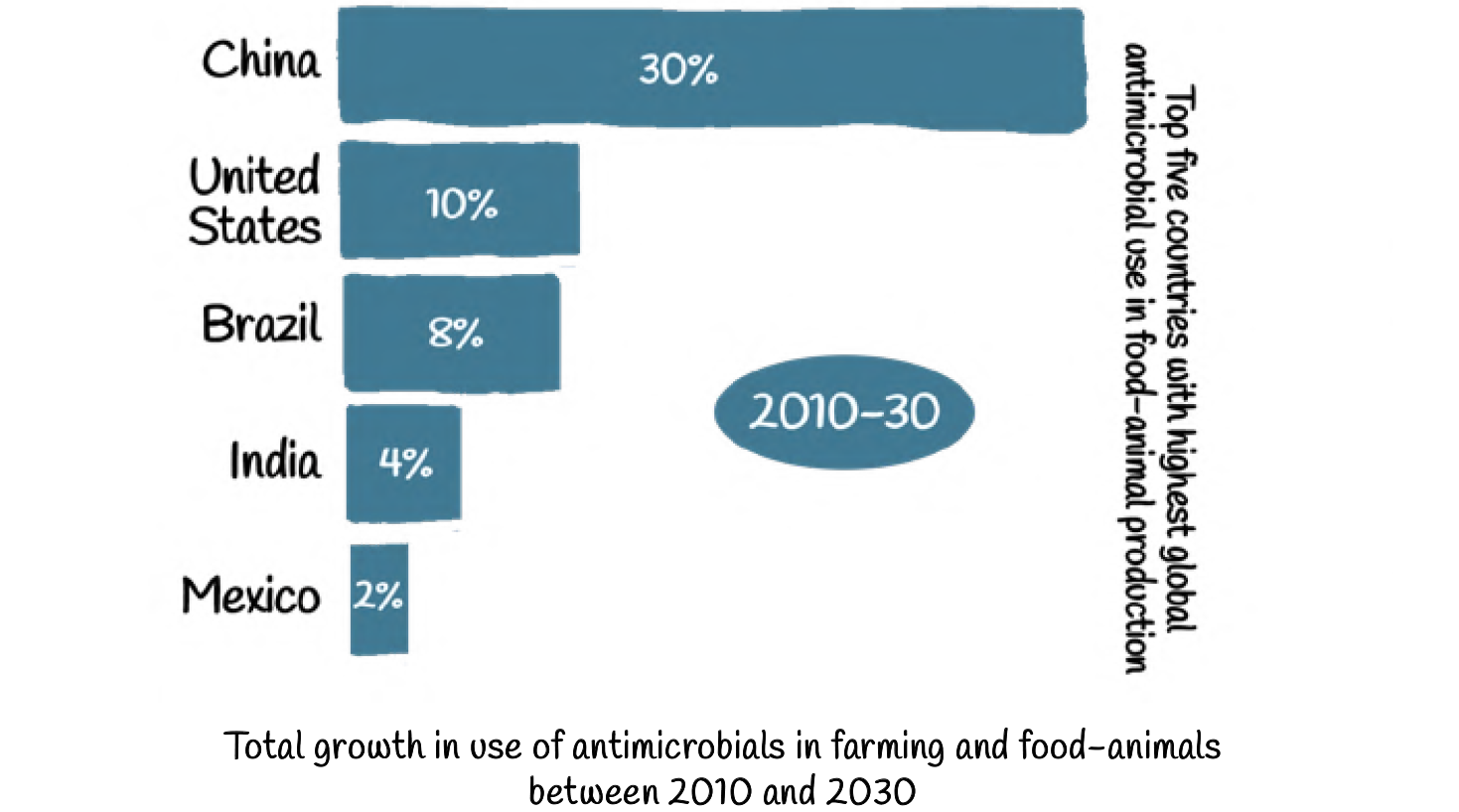

The consumption of antimicrobial drugs in the food-animal sector is however not uniformly distributed throughout the world.

Antibiotic consumption is also expected to rise significantly in several developing countries by 2030 due to increasing meat consumption.

By then, the BRICS countries — Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — alone will witness a projected increase of antibiotic consumption by 99 percent.

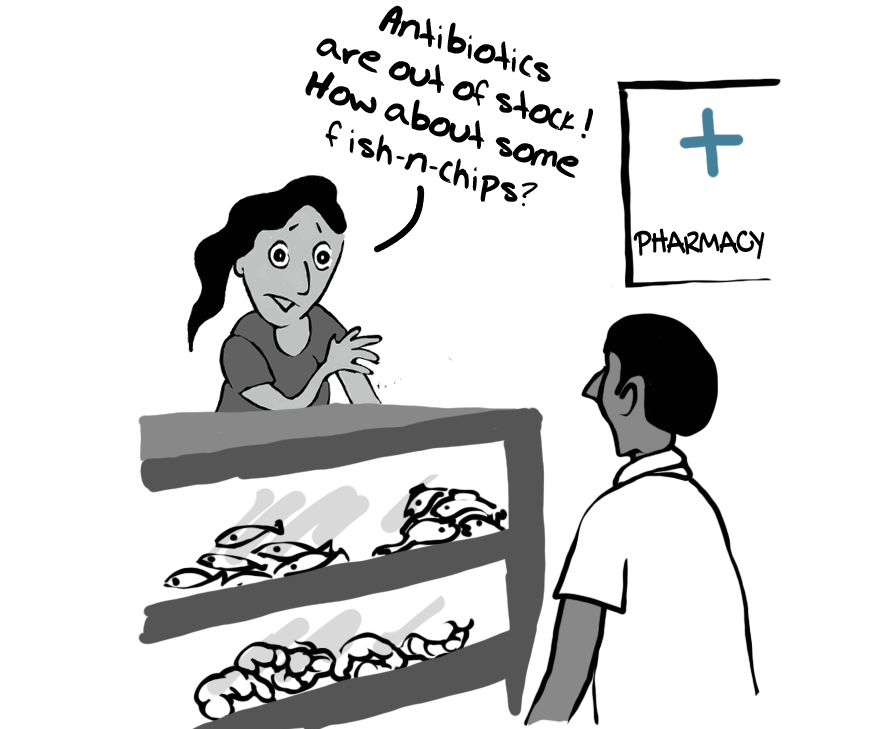

When it comes to antibiotic use, aquaculture, which is growing faster than any other food-animal sector, also seems to be a significant contributor to the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

What are the alternatives?

While many producers and farmers justify antibiotic use in their food-animals as being ‘unavoidable’ there is considerable research that shows the production gains can be achieved by other means too.

Alternatives to non-therapeutic antimicrobial use range from changing production practices to using various substitutes. These include more environmentally sustainable systems, where a higher emphasis is placed on animal welfare and disease prevention through hygiene, vaccination and intelligent herd management.

Changes in production practices that reduce the need for non-therapeutic antimicrobials might include altering the weaning period, lengthening the feeding time, or improving sanitary and hygienic conditions. Substitutes for antibiotic therapies include vaccines, micronutrients, and other non-antimicrobial fortified feed such as for example, fish oils. One of the commonly considered strategies, drawing from the experience in Denmark, is improvement in hygiene and reduction in stress through changes to the production methods, density of animals in each farm and better sanitation.

Other changes to production practices include cleaning facilities, improving ventilation and switching from gestation crates to pen system for swine.

By changing the environment and by decreasing the stocking density, producers can reduce the stress and disease transmission as well as improve control of temperature, humidity and hygiene in ways that benefit animal health. A combination of compulsory and voluntary actions with clear reduction goals resulted in a 56% reduction in antimicrobial use in farm animals in the Netherlands between 2007 and 2012.

While such changes may require initial high capital investment costs and moderate resource inputs over time, they are among the most effective of the alternative strategies and help decrease the selective pressure to use antimicrobials for production or prophylactic purposes.

Antimicrobial residues in food

Unregulated and excess use of antimicrobials in the animal sector often means that withdrawal times, i.e., the time between last antimicrobial treatment and marketing of food from the treated animal, are not respected. This can lead to higher than acceptable levels of antimicrobial residues in the food product.

For example, a study in Ghana showed that the prevalence of drug residues in animal source food was 20%. In fish and shrimp bought at a regional market in Vietnam, antimicrobial residues were found in 25% of the screened samples. In these cases, antimicrobial use is also a food safety issue.

However, while residues can be detected even in very small quantities, they are not inevitably toxic. The amount of residues needs to be related to evidence-based threshold limits to evaluate their potential impact on our health.

One Health Approach

One of the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, that has devastated lives and economies throughout the world, is greater public awareness of the link between human interaction with animals and the transmission of dangerous new pathogens.

While the emergence of a virus like COVID-19 is a relatively rare event, on a more routine basis the extensive use of antibiotics in farming of food animals produces antibiotic resistant bacteria that may lead to therapy failure with a negative effect on animal health and welfare.

The link between human, animal and environmental health is captured in the concept of One Health. This concept is now the basis of an important global movement that brings together human, veterinary and wildlife health communities to take a more coordinated approach to disease and epidemics in general.

The areas of work in which a One Health approach is particularly relevant include food safety, the control of animal diseases that can be transmitted to humans and combating antimicrobial resistance.