Before we go any further to learn more about antibiotics, it is time to take a pause and ask some questions about their prime target – the bacteria.

Instead of assuming we know everything about them (‘evil, disease- causing microbes’) what if we started with a completely open mind and asked – so what exactly are bacteria supposed to be?

When they were discovered by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1676, he thought of them as animalcules, meaning tiny animal in Latin.

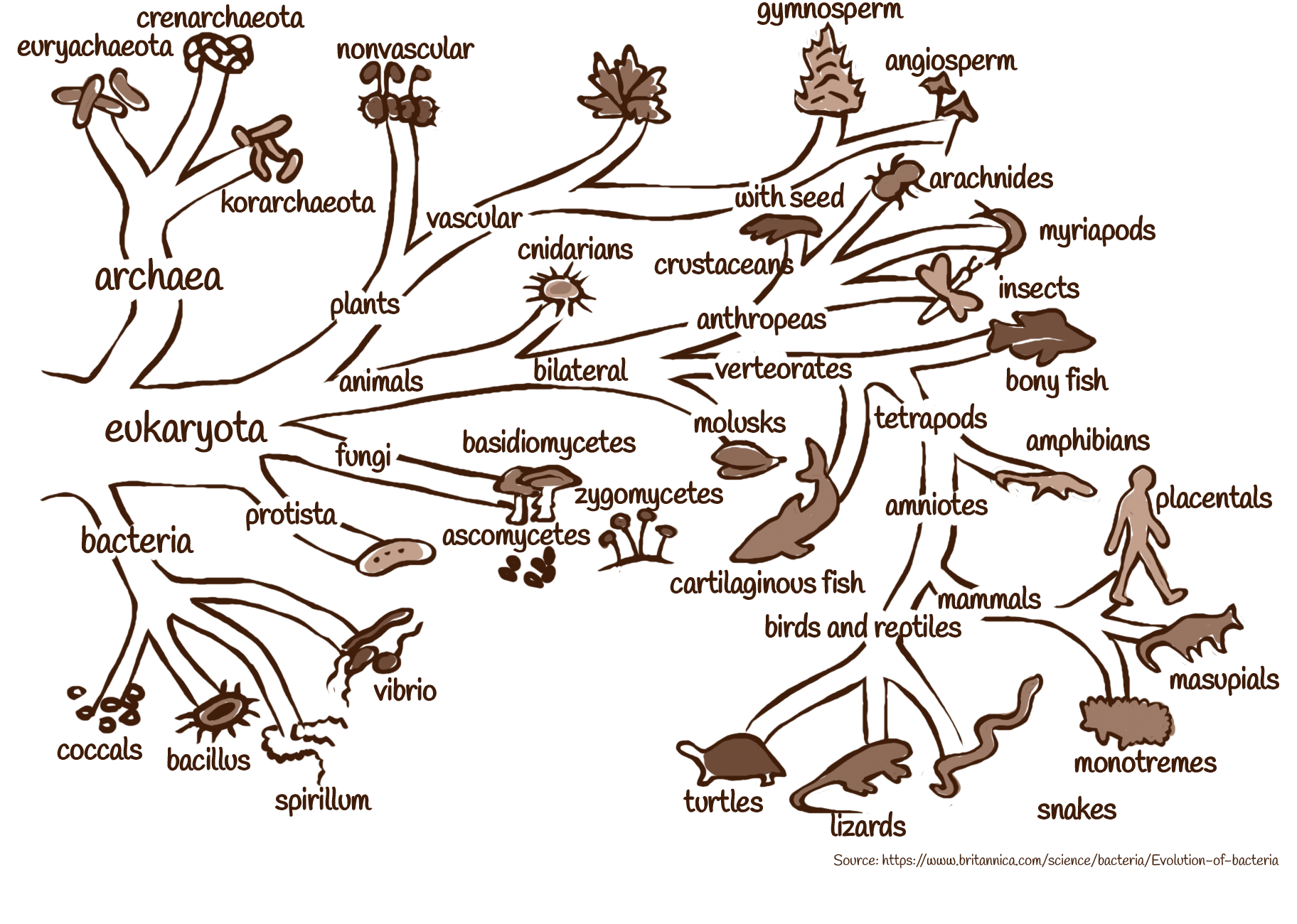

For a long time bacteria were classified according to their basic shapes into five groups: spherical (cocci), rod (bacilli), corkscrew (spirochaetes), comma (vibrios) and spiral (spirilla).

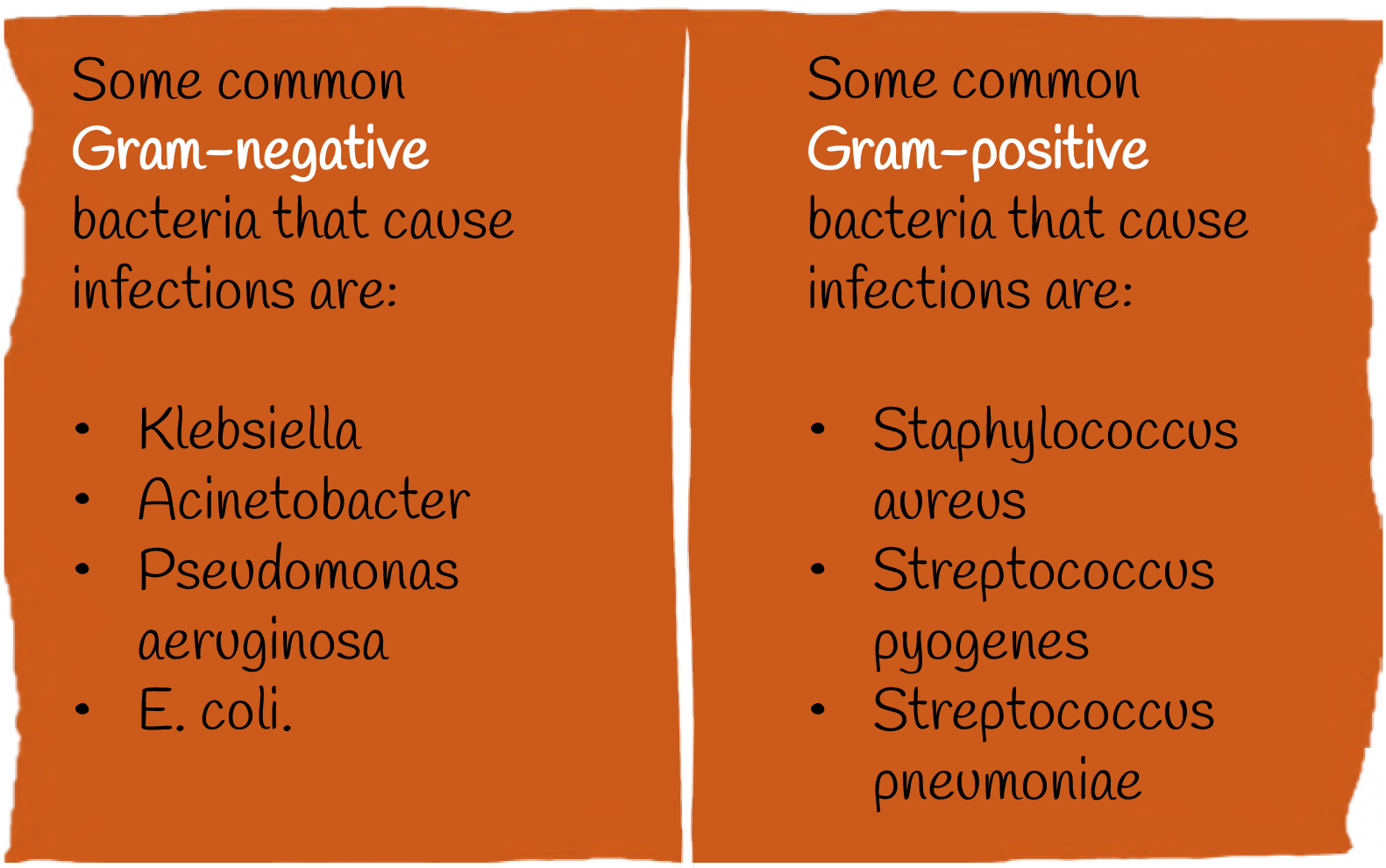

Bacteria are generally classified into two broad categories: Gram- positive and Gram-negative.

The term “Gram’ here comes from Hans Christian Gram – the name of the person who developed the method for distinguishing between these two types of bacteria.

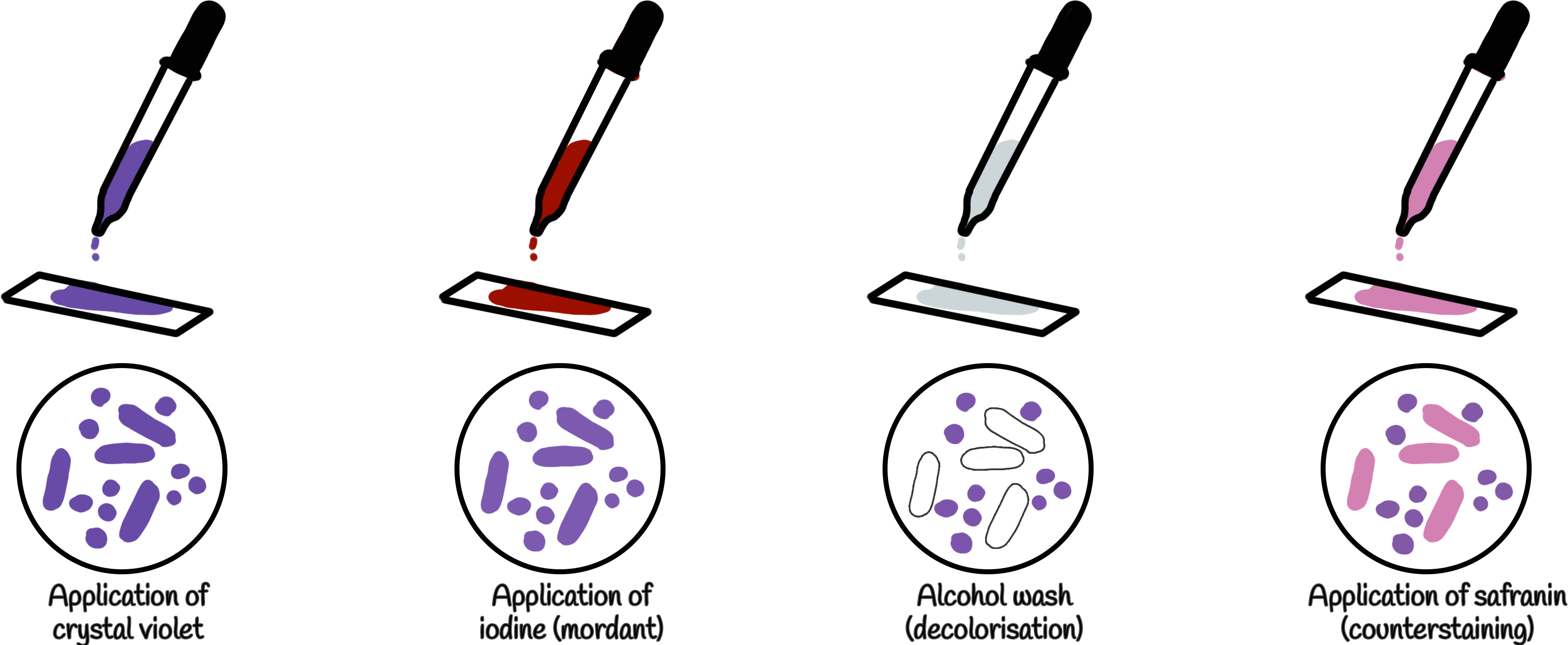

The differences between Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria are primarily related to their cell wall composition. The staining method that Dr Gram introduced identifies bacteria based upon the reaction of their cell walls to certain dyes and chemicals. Gram- positive bacteria stain purple after Gram staining. Gram-negative bacteria stain red or pink.

In the last couple of decades new methods of studying bacteria have emerged, such as polymerase chain reaction or PCR, also sometimes called molecular photocopying.

The process involves rapidly making billions of copies of a specific DNA sample and amplifying them to allow scientists to and study them in detail and understand their origins and characteristics. This has completely revolutionized our understanding of these invisible organisms.

First of all it turns out there are a vastly greater number of species of these invisible organisms than anyone imagined even a couple of decades ago.

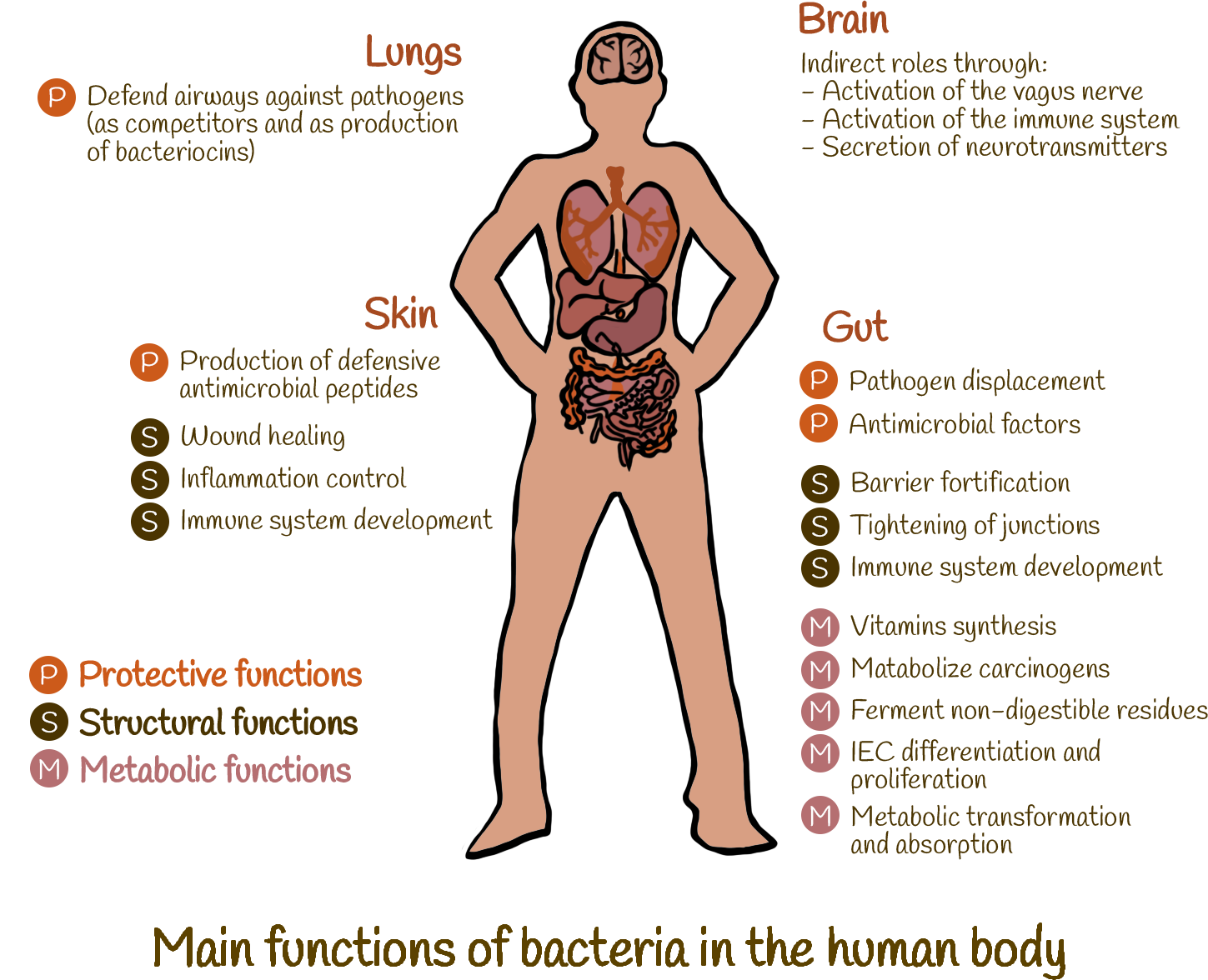

Secondly, they are found everywhere on the planet – from flaming hot volcanoes to the permafrost in Siberia. They also exist in a very large number inside the human body and are critical to not just our survival but

that of all life forms on earth.

Till not too long ago scientists believed there were about 30,000 formally named species that could be cultured in the laboratory and for which the physiology had been investigated. Now they are not sure any more and thanks to newer diagnostic techniques, estimates for the number of bacterial species run from around half a million to a billion plus.

There is also a continuous debate on whether bacteria, many of which constantly exchange genetic material between themselves, can even be classified in terms of many distinct species. Some have suggested bacterial cells are simply holding vessels for the genetic variation available in the bacterial gene pool, which change according to different environments.

The point here is that the world of bacteria is quite complex, diverse and not reducible to simple black and white type of characterisation.

Yes, a small number of them do cause deadly diseases, under specific circumstances, but the vast majority form the very basis of all life and living processes on Planet Earth. The insight being expressed by a range of researchers – from microbiologists and chemists to ecologists and origin of life specialists – is very clear, that we live on a planet that is run by millions of bacterial species.

They were among the first forms of life on Earth, and are its most numerous living organisms.

The facts and figures involved are stark!

a) Bacteria have been around for roughly 4 billion years on a planet that is 4.5 billion years old. They have not only survived the harshest weather, toxicity and abrupt shifts in environment, but have time and again contributed to mitigating these factors and making them conducive to the flourishing of life.

It is time we paid some respect to bacteria and stopped demonizing them!

b) Collectively bacteria account for around 70 gigatons of carbon in biomass distributed among all of the kingdoms of life. This is much greater the carbon in biomass of all the animals on the planet (including humans) put together, which constitute only 2 gigatons. (Plants still dominate the planet with 450 gigatons of carbon.)

In other words, humans and other animals are essentially swimming in an ocean of bacteria – we have to learn to live with that reality.

c) The amount of microbes in the human microbiome is higher than the number of cells in the human body. The total microbial biomass in an average adult is approximately 0.2 kg. The microbiome today is considered another organ of our bodies.

So trying to destroy all the bacteria in your body is nothing less than trying to willingly injure yourself!

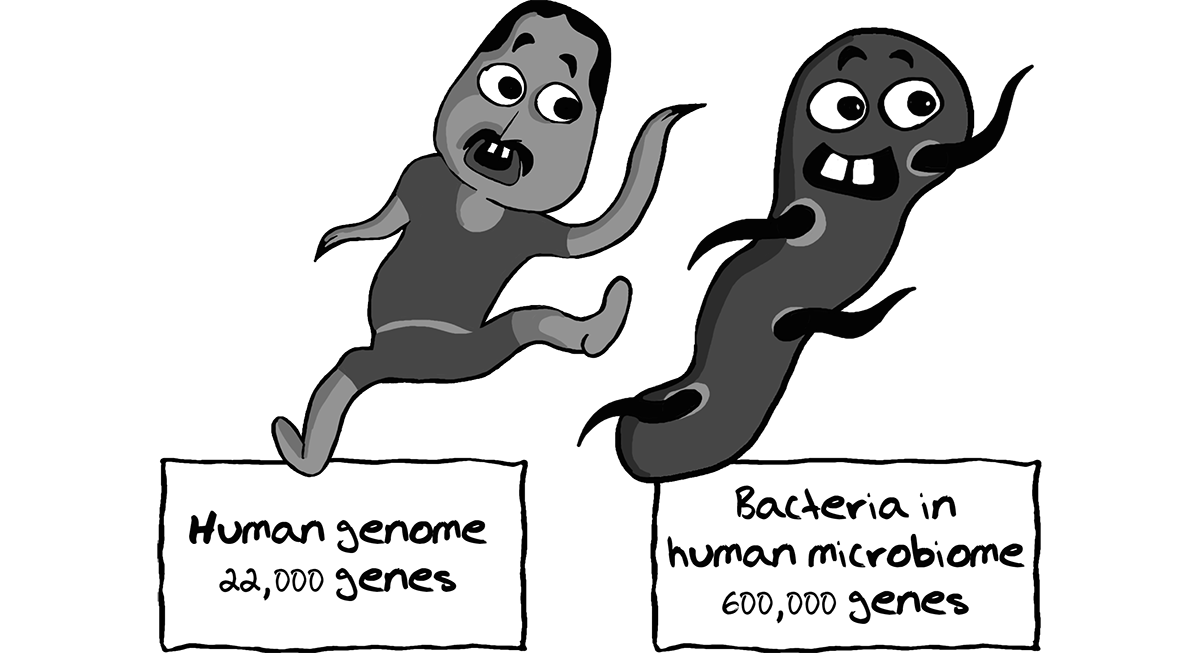

d) More importantly, bacteria in the human microbiome contribute around 600,000 genes, way more than the human genome’s 23,000.10 We are yet to figure out how all this bacterial genetic material affects our health and lives. And while scientists are still trying to figure out this mystery it is best that the rest of us go a bit slow on popping those coloured pills whenever we feel like!

To summarize, bacteria are phenomenally diverse, essential for survival of all life forms, and highly flexible and adaptable in the face of all challenges. These are all remarkable traits that we humans would do well to emulate.

Our very survival may depend on it!