Antibiotics present an interesting paradox: The more we use them, the less effective they become. And the less effective they become, higher the dosage in which we are forced to use them!

Antibiotics are just like fossil fuels – a non-renewable and finite resource. Just as the burning of these fuels has contributed to global warming and impending climate catastrophe – the use and abuse of antibiotics is spreading bacterial resistance with all its dire consequences for human health!

Yes, it is essential to use antibiotics to save the lives of people affected by severe bacterial infection. It is important to keep in mind though, that sooner or later, bacteria will evolve to defeat the antibiotics we have. This means that we will always need to find new drugs to fight bacterial infections.

Rising demand, dwindling supply

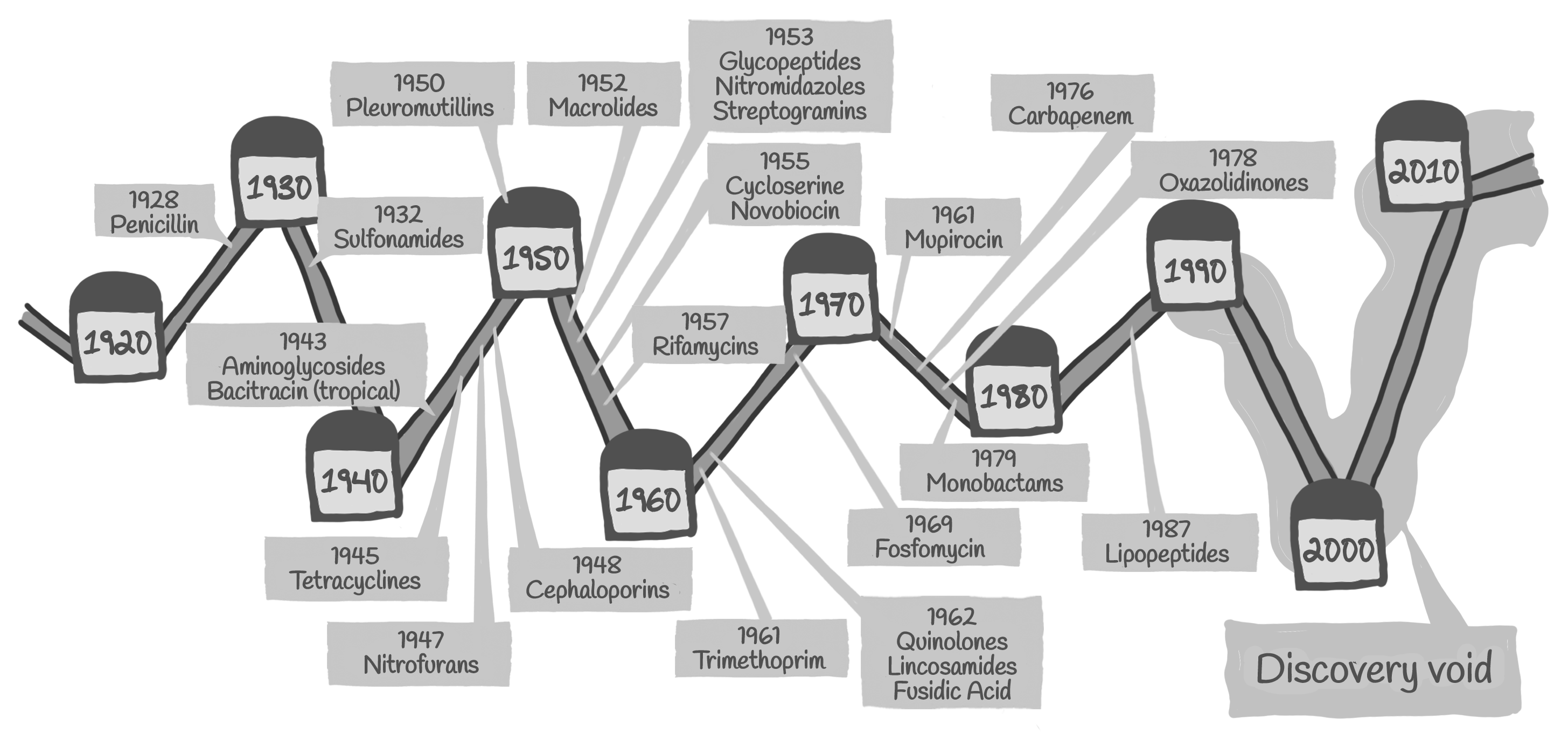

However, today there are too few antibiotics being developed to meet the growing need. The last time scientists discovered a truly new class of antibiotics that made it to market was in 1987.

At the same time resistant bacteria that survive antibiotic treatment are becoming more and more common, making available antibiotics ineffective. We have reached a point where there are hardly any treatment alternatives left for some bacterial infections.

Especially worrisome is the lack of antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria, which cause some deadly infections such as pneumonia and meningitis.

So, why can’t we find new antibiotics? Here are some of the reasons:

It is extremely difficult to develop an antibiotic. First, like all drugs, it needs to get to the right place in the body at a high enough concentration without being toxic to the patient.

Then, it also has to enter and stay in the bacterial cell, which has proven very problematic. Efforts to screen large existing libraries of small molecules or use genomic sequencing have failed to find new antibiotics.

Much of the problem seems to lie in the early stages of antibiotic development. For example, we, the antibacterial drugs are estimated to have a ten-fold lower yield in the discovery stage of identifying promising new compounds when compared to all drug classes.

These scientific difficulties have been compounded by several external factors. This includes the reality that most multinational pharmaceutical companies have exited the anti-infective field due to commercial returns being less than other therapeutic areas.

Over the last three decades, the number of multinational companies with active anti-infective programs has fallen from 18 to just 6 in 2020.

• The Pharma industry’s priorities

There is a mismatch between the infectious diseases which most urgently need new antibiotics and the drugs that are currently being developed.

A recent analysis showed that of the 50 candidates in clinical development only two are targeting high priority multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria, which are spreading at worrying speed and urgently require novel treatment options.

In other words, the pharma industry has a business model which ensures higher returns on investment. The collateral damage to this approach is the lack of R&D in newer antibiotics which is the real need of millions of patients who require effective antibiotics in a situation of rising bacterial resistance.

• The market-based model is not working

It is very expensive and often takes ten years or more to develop an antibiotic. The market-based model for financing late stage clinical development of pharmaceuticals relies on companies recouping their R&D costs through sales of the end-product.

This means the model relies on charging high prices and an incentive to sell as much as possible within 20 years before patent protection runs out.

Both features are undesirable for new antibiotics given that both affordable access and stewardship are required to preserve the drug’s effectiveness. For these reasons, the “traditional” market model has not brought forward novel antibiotics for decades. Overcoming all these challenges is not going to be easy. A good beginning would be however for policy makers to encourage policies which prioritize public health and the needs of the population.