Reducing overuse of antibiotics is key to tackling antibiotic resistance worldwide. Lesser the amount of antibiotics used, the smaller the chance of bacteria becoming resistant to them.

However, this important goal has to be seen in the context of how even eight decades after their discovery, a vast number of people do not have access to these life-saving medicines.

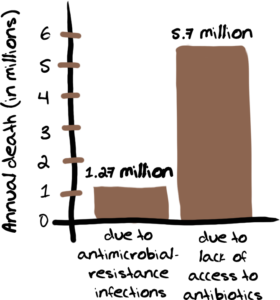

Every year there are over 5.7 million deaths that could be averted with access to antibiotics. Yes, that is a huge number and one that is much bigger than the estimated 1.27 million lives lost annually due to antimicrobial-resistant infections.

Not surprisingly, the majority of these deaths due to lack of access to antibiotics occur in low and middle-income countries.

Ensuring universal appropriate access to antimicrobials is not only a critical part of realizing the RIGHT TO HEALTH, but is necessary for mobilizing effective collective action against the development and spread of antibiotic resistance.

In other words the challenge of dealing with the growing problem of antibiotic resistance is not just about restricting inappropriate use of these valuable drugs. It is also about providing them to people who cannot get them when they really need them.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed many systemic and deeply unacceptable global health inequalities. The most glaring example is the way some rich countries get access to vaccines and other important medicines first, and poor countries are left depending on charity.

The situation is not very different in the context of antibiotics. Poorer countries, with a high burden of bacterial infections, are often the last to gain access to effective antibiotics.

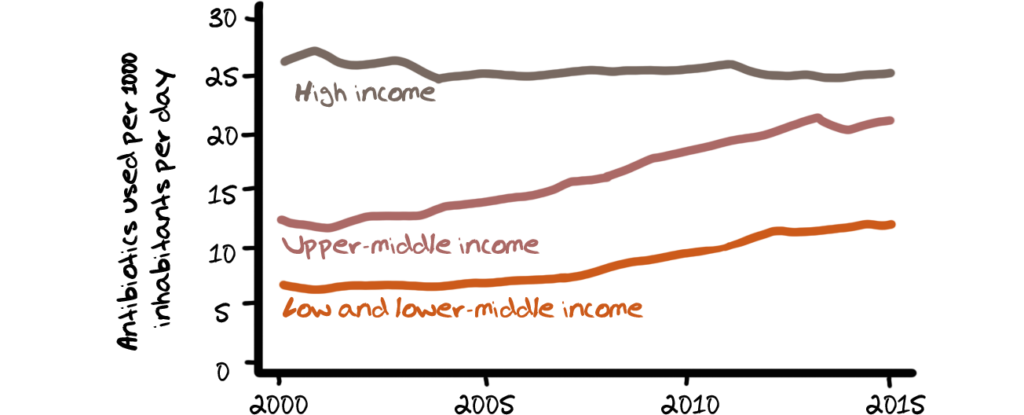

According to the OECD, 50% of prescriptions for antibiotics in high income countries are unnecessary and antibiotic consumption in HICs, as depicted in the charts below, is more than double that in low-income countries measured in defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day.

High costs

In many low and middle-income countries, even when antibiotics are available, patients are often unable to afford them.

This could be due to high levels of poverty in general but also limited government spending for health services.

The absence of universal health care or even reasonably priced health services results in high out-of-pocket medical costs to the patient.

Such expenditures push some 38 million people into poverty each year in India alone. A decade ago in India, the median overall additional cost to treat a resistant bacterial infection was US$ 700, which equalled 442 days of work pay for the average rural male worker. Currently, the burden may be worse.

Shortages in public health facilities force patients to go to private pharmacies to buy medicines that should have been provided free in the first place. Individuals may also self-medicate with antibiotics sold over-the-counter at the pharmacy or in the informal market. Others forego medication altogether, worsening the burden of bacterial infections in these countries.

Health systems

The responses sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic involved collaboration for rapid innovation of diagnostics and vaccines to implementation of preventive measures and equitable access to essential medicines and basic supplies. The same perspective needs to be applied to antibiotic resistance.

In other words, a more holistic health systems approach for sustainable access to antibiotics is required. A fragmented approach is ineffective.This implies, among other things, concerted efforts towards human resources, universal health care, and optimal health-care infrastructure.

For example, a third of health-care facilities in low-resource settings have little access to running water and soap for handwashing.

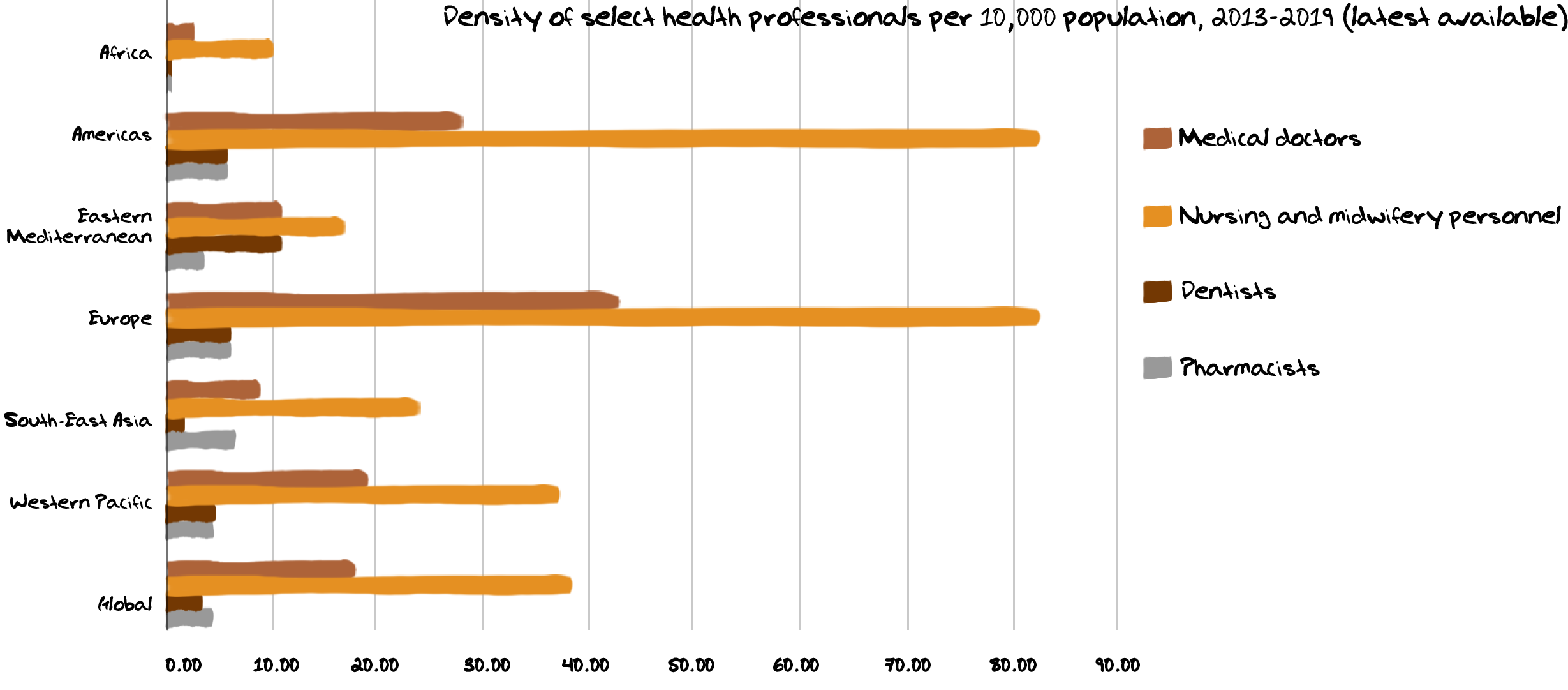

Health facilities in many low and middle-income countries are substandard and lack staff who are properly trained in administering antibiotics. Inadequate staffing makes it difficult to administer medicines and patients miss antibiotic doses, once again compounding the problem of resistance.

Just the mere existence of an effective antibiotic does not mean that they are available in countries where they are most needed. Most new antibiotics emerge from public or private labs in high income countries that have the skills and resources needed for the research and development required. While these new antibiotics are registered for use in these countries, they often do not reach low and middle income countries. This could be because these markets are seen as not being lucrative enough or ‘difficult’ to operate in.

For example, among novel antibiotics entering the global pharmaceutical market between 1999 and 2014, registration was mostly concentrated in high income countries. Only 12 of 21 products were registered in more than ten countries. For novel antibiotics introduced since 2014, registration has been filed in fewer than five countries per year, slowing down approval and use.

Supply chain problems

The current global supply chain is fragile and relies on only a few producers of active pharmaceutical ingredients and manufacturers based in a few countries such as India and China. For some antibiotics, there are just one or two major producers and disruptions therefore lead to global stockouts and shortages. The entire chain of producers, suppliers and marketers are also not transparent making it difficult to get an accurate picture of specific ways to resolve problems.

In low and middle-income countries, weak drug supply chains make the consistent availability of antibiotics a problem. Maintaining quality of medicines is also a problem, with researchers finding that many products were stored and transported long distances without cold-chain temperature control.

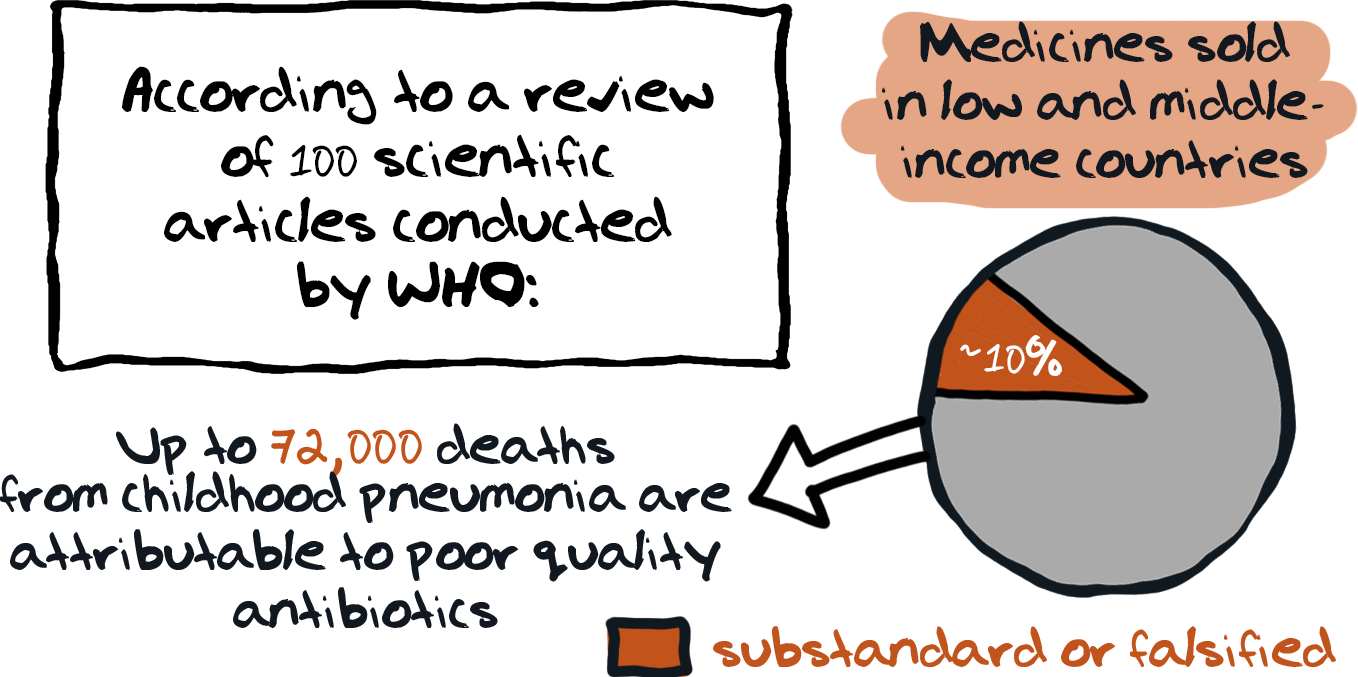

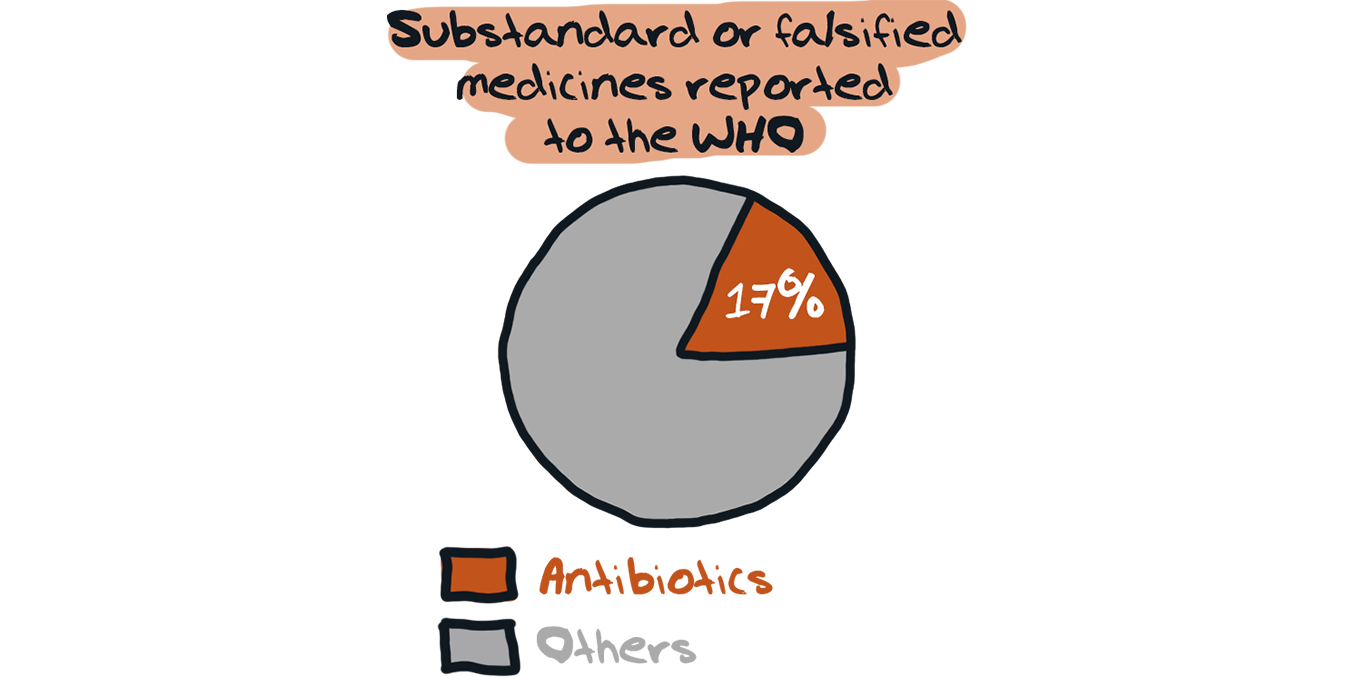

Lack of oversight and regulation in the drug manufacturing and supply chain leads to poor drug quality and falsified medicines.

Many national drug regulatory authorities are also unable to assess the quality, safety, and efficacy of older antibiotics that are registered, and which may be substandard or falsified.

Lack of oversight and regulation in the drug manufacturing and supply chain leads to poor drug quality and falsified medicines.

Many national drug regulatory authorities are also unable to assess the quality, safety, and efficacy of older antibiotics that are registered, and which may be substandard or falsified.

Regulation

Limiting the sale of antibiotics to prescriptions seems like an easy solution and functions well in some countries. However, enforcing prescription-only laws may cut off access to antibiotics for parts of the population. This is particularly so in rural areas and in resource-limited settings that lack access to prescribers.

What can be done?

- National governments, policymakers;

- Pharmaceutical companies;

- Public and private healthcare institutions;

- International public health bodies.

This is not an exhaustive list of course. Some of the steps needed to address key barriers to accessing antibiotics include:

• Encouraging research and development of new or improved antibiotics, diagnostic tests, vaccines, and alternatives to antibiotics for bacterial infections;

• Supporting the registration of antibiotics in more countries according to clinical need;

• Developing and implementing national treatment guidelines for the use of antimicrobials;

• Exploring innovative funding for essential antibiotics;

• Ensuring the quality of antibiotics and strengthening pharmaceutical regulatory capacity;

• Encouraging local manufacturing for cost-effective antibiotics;

• Developing a system of global rules-based governance as a framework for solutions to all these challenges.